Is IBM Prepping Power8 For Late April Launch?

IBM has been telling Wall Street and customers to expect its Power8 processor and the initial systems using them to launch sometime around the middle of this year, but it looks like they may get here a little bit earlier if the rumors running around are right.

According to sources who are familiar with Big Blue's plans, the initial Power8 machines are slated to be launched sometime in late April or early May. There is a lot of chatter at the moment and a date has not emerged yet from the noise.

Historically, IBM likes to do system launches in April, which gives it time to book some initial sales before the second quarter ends and ramp up the product line and shipments as the year progresses towards the fourth quarter. There is not a precise pattern to IBM's Power Systems launches, but it often does a launch in the midrange part of the line in April or May and then rolls out entry and high-end systems in the fall. IBM pulled the Power7 launch in the midrange into February 2010 to coincide with a bounce-back in server spending in the wake of the Great Recession, a launch that was originally scheduled for May of that year. The Flex System modular systems and their PureSystems variants came out in April 2012. The Power Systems entry and midrange systems were boosted with Power7+ chips last February.

If there is a pattern in recent years, it is this: If new systems do not come in February, they come in April. February has come and gone with no Power8 announcements, and so all eyes in the Power Systems space are looking at April. Business partners will be briefed in the coming weeks, and word will eventually get out about the precise launch date.

That late April date is probably not an accident. IBM is hosting its Impact 2014 customer and partner conference in Las Vegas from April 27 through May 1. The agenda includes tracks dedicated to PureSystems converged platforms as well as System z mainframes and does not talk about Power8 iron. IBM did host a customer and partner event in Kansas City on February 18 where it did talk about Power8 systems and the tighter collaboration between its Software Group and Systems and Technology Group with this class of machines. IBM is also inviting techies to come to its Austin, Texas Power Systems lab for a residency to learn about the new systems and help put together documentation for the machines; these residencies run from March 24 through April 4, and they are a precursor to an impending announcement.

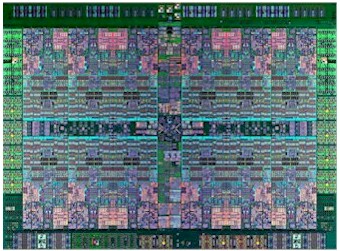

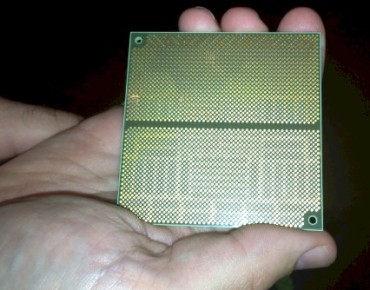

IBM showed off the Power8 processors at the Hot Chips conference at Stanford University last summer. The chip, which is implemented in a 22 nanometer process, is manufactured by IBM's own Microelectronics division in its East Fishkill, New York chip plant. In the wake of IBM's deal to sell off its System x division to Lenovo Group for $2.3 billion in January, there are rumors that Big Blue might be considering selling off its chip manufacturing business and that it has hired Goldman Sachs to help it explore its alternatives. Even if IBM does sell off its chip making business, it will no doubt continue to design Power and mainframe processors and sell systems that employ them. It makes too much money off of the software that runs on these systems. The same cannot be said of X86 machinery, where Intel, Microsoft, and Red Hat get most of the profits and the X86 system vendors live on razor-thin margins.

The Power8 chip crams a dozen cores running at between 2.5 GHz and 5.5 GHz (in lab conditions) onto a single die, with 96 MB of L3 cache shared by those cores. At a 4 GHz baseline speed, a Power8 core will offer about 1.6 times the performance per thread as a Power7 core running at the same speed, and a Power8 socket at that same 4 GHz baseline will offer between 2X and 2.5X the aggregate application throughput compared to a Power7+ socket. This is a pretty significant bump in performance, which is enabled in part by microarchitecture changes in the core and by the shrinking of manufacturing processes from the 45 nanometer used with the Power7 chips and the 32 nanometer used with Power7+ chips. IBM will also be doubling up the simultaneous multithreading (SMT) with the Power8 chips to eight threads per core, squeezing even more performance out of each core for those workloads, like databases and Java, that like to chew on lots of threads.

It has been quite a long time since IBM substantially altered the form factors for its Power Systems machines. It has 1U and 2U rack-based entry machines with tower variants aimed at small and medium businesses as well as 4U systems that can be lashed together to create multi-node NUMA machines. With motherboard and hyperscale system maker Tyan being a member of the OpenPower Consortium, there is a distinct possibility that a new set of low-end machines with a more modular design could come out with the Power8 machines. And possibly not only from Big Blue. For all we know, IBM will be using motherboards made by Tyan in its own systems, and hence the relationship that the two have through the OpenPower Consortium. (IBM has not said where it gets its motherboards for Power7 and Power7+ machines, and for all we know, a third party has been making them for years.)

We also know that Google, another OpenPower Consortium member, has been testing its own homegrown Power8 systems in its labs. It is highly unlikely that Google would share its designs with anyone else, or discuss its plans for Power-based systems, unless it suited one of its own needs. For instance, just saying that Power-based machines might be an alternative to X86 iron gives Google some leverage with Intel.

IBM's own NextScale vanity-free machines for hyperscale customers could be modified to support Power8 chips, as could the just-announced System X6 machines that use Intel's Xeon E7 v2 processors. It would not be surprising at all to see Power8 machines that look very much like these machines. IBM will, of course, create Flex System nodes based on Power8 for its PureSystems converged systems. Thus far, IBM has created two-socket and four-socket nodes for PureSystems, but it could do uniprocessor and eight-socket variants as well. It all depends on how densely IBM can pack the memory in next to the Power8 chips.

At the top-end of the Power Systems line, IBM has mainframe-class NUMA machines that scale to 32 sockets in a single system image. The Power7 and Power7+ interconnect has five NUMA links to maintain cache coherency across up to sixteen sockets in that multi-node NUMA machine, which connects the nodes gluelessly as they say in the industry. Moving up to 32 sockets in the Power 795 machine requires an external node controller chipset. With the Power8 chip, IBM has six serial links on the NUMA interconnect electronics, and that means IBM can probably connect up to 32 sockets gluelessly now. Big Blue could also use that extra NUMA link to push scalability up to 48 sockets, and maybe even higher if customers want it. A 48-socket machine might be able to push the performance of a top-end Power System machine up by a factor of four or five times, depending on the clock speed of the processors and the efficiency of the interconnect.